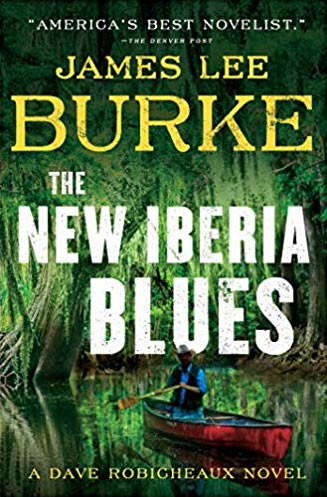

![]() New Iberia Blues – James Lee Burke Published January 2019 by Simon and Schuster, 465 pages of pure scenic detective fiction. I checked my copy out from the library and I sure wasn’t disappointed with this. This is the book I had in mind when I was reading Debbie Herbert’s Cold Waters. There are several threads running through this story and its woven together masterfully.

New Iberia Blues – James Lee Burke Published January 2019 by Simon and Schuster, 465 pages of pure scenic detective fiction. I checked my copy out from the library and I sure wasn’t disappointed with this. This is the book I had in mind when I was reading Debbie Herbert’s Cold Waters. There are several threads running through this story and its woven together masterfully.

Detective Dave Robicheaux spies a woman tied to a cross drifting in from the bay while on the deck of his old friend Desmond Cormier’s house. The award winning director Desmond and company are in the area filming a new movie when a series of unfortunate incidents occur. From a dead woman on a cross, to a hanged laborer, then a crooked sheriff’s deputy is killed… as Robicheaux diggers deeper into the people surrounding Desmond the bodies pile up.

Is there a killer amongst Desmond’s friends or could it be a fugitive death row inmate from Texas who has been spotted in the area… or perhaps its an albino mafia contract kill whose also returned to New Iberia. It couldn’t be a young deputy who has a knack for being around just when someone is killed… could it?

The descriptions are wonderfully drawn in a vibrancy of detail and oe of the things that I liked about this story is that there is time in between the events. Everything isn’t cramped together, its spaced out, paced over a series of months, season even. The story starts in the spring and concludes in the fall and Burke gives amble nuanced description of the bayou throughout its transitions.

And its not just the physical landscape, no, the characters themselves are painted with a fine-tip brush. Even the recently deceased get rendered in full dimension:

By Monday the victim had been identified through his prints as Joe Molinari, born on the margins of American society at Charity Hospital in Lafayette, the kind of innocent and faceless man who travels almost invisibly from birth to the grave with no paper trail except a few W-2 tax forms and an arrest for a thirty-dollar bad check. Let me take that one step further. Joe Molinari’s role in life had been being used by others, as a consumer and laborer and voter and minion, which, in the economics of the world I grew up in, was considered normal by both the liege lord in the manor and the serf in the field.

He’d lived in New Iberia all his life, smoked four packs of cigarettes a day, and worked for a company that did asbestos teardowns and other jobs that people do for minimum wage while they pretend they’re not destroying their organs. He’d had no immediate family, played dominoes in a game parlor by the bayou, and, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, never traveled farther than three parishes from his birthplace. He had gone missing seven days ago.